–Published in Whole Life Times Magazine in August 2011–

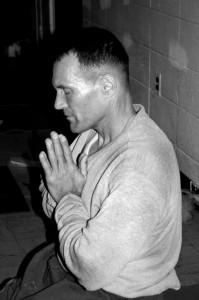

Like most war veterans, Barry Schweiger chose not to seek psychological treatment when he returned from active duty.

“We’re taught in the military to endure pain and hardships, and to be incredible warriors. But many people are forced into that role,” says Schweiger, and when soldiers return home, it’s often difficult for them to seek help or admit they’ve suffered psychological and emotional trauma. “In the eyes of the military, that would be viewed as a weakness, so they just suffer through it.”

Which is exactly what Schweiger did when he came home from Vietnam. As a result, over the next 25 years his anger, hostility and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) caused him to alienate not only his wife and children, but coworkers as well.

And then everything changed when, on a whim, he attended a beginner’s yoga class at his gym.

“Yoga turned out to be exactly what I never knew I needed,” he jokes. “The beauty of it was the slow process, the quietness, and the simplicity of just doing the poses. Anything faster, louder or more strenuous would have killed me. What I needed to do was slow down and learn how to be with myself, not run away from everything going on inside me.”

Now, 15 years later, Schweiger is a certified yoga teacher at Yogaloft in Woodland Hills teaching a class every Friday called Yoga for PTSD. Through his practice he’s been able to work through many of his issues, and hopes to help others do the same.

“I got into being a yoga teacher not just because I wanted to be a teacher, but because I wanted to be a trauma sensitive yoga teacher,” he says. “Yoga is a tremendous way to restore one’s soul, essence and control of the body, and my goal is to help people achieve this.”

Who Gets PTSD

Veterans aren’t the only people who suffer from PTSD. It is a wide-ranging anxiety disorder that may be triggered by any number of events that pose a threat of harm or death. According to a 2005 study from the Archives of General Psychiatry, approximately 7.7 million American adults ages 18 and older (or 3.5 percent of this age group) have PTSD. And while war veterans are the most likely candidates, any type of traumatic event, such as child abuse, sexual abuse, domestic violence, natural or human-caused disasters, or a life-threatening illness can trigger it.

PTSD has traditionally been treated through psychotherapy, but recently physical approaches, such as yoga, have been studied. In his book Overcoming Trauma Through Yoga (North Atlantic), co-author David Emerson (with Elizabeth Hopper) discusses the importance of treating not only patients’ minds, but also their bodies, where memories of traumatic events are stored. They write, “While talk-based therapy serves a critical role in the healing process, many are finding that it is insufficient by itself.” Yoga and other forms of therapeutic physical activity may be the missing link.

Emerson has been teaching yoga classes to a broad range of students with PTSD for eight years.

“I’ve taught yoga to people with substance abuse and drug addiction problems, kids from abusive households or dangerous neighborhoods, rape victims, kids in gangs, ex-convicts, people who engage in self-harm, like cutting . . . you name it,” he said in a phone interview. “But they all have one thing in common: they’re all trying to deal with having to live in their body and feeling totally alienated from it following trauma.”

This, he explained, is why you can’t treat PTSD solely through talk therapy. The body can’t help but have a physical response—increased heart rate, tense muscles, rapid breathing—to trauma. The emotional pain and traumatic memories of the events are then stored somatically, and although they may manifest in psychological symptoms, such as flashbacks, anxiety, hypervigilance and dissociation, they are rooted in the physical body.

“As you grow, these feelings and memories take root in your body, and any type of sensation, whether it’s muscles flexing or stretching, can become associated with trauma,” Emerson explains. “I’ll often hear people tell me they can’t feel their legs or that part of their body is numb. Or that they panic when anybody touches them and can’t even let their kids touch them because it evokes too many memories of abuse.”

Yoga students with PTSD may even have difficulty surrendering in savasana or relaxing in child’s pose because of the feelings of vulnerability they evoke. Emerson reminds students that they should only do what feels comfortable to them. “We want people to have a safe experience, to become friendly with their bodies, and rebuild trust and comfort with the physical self,” he says.

It’s a very different approach from traditional talk therapy. “We’re not talking about emotions or analyzing them,” says Schweiger. “There’s no intellectualization, you just let them happen.” Indeed, when Schweiger first started doing yoga he noticed a bubbling up of anger that he’d never before recognized. “It was only when I started doing the poses, slowed down my breathing, and really just learned to deal with being still in my own body that these emotions came out,” he says. “Sitting in a chair and talking to a shrink might not have done the trick.”

Tangible Benefits

Even something as simple as mastering the asanas can have an empowering effect. James Fox, founder of the Prison Yoga Project, which hosts yoga and mediation classes at rehab facilities and prisons throughout Northern California, has found that yoga helps people develop qualities and skills they may not have known they had.

“They realize they can deal with the pain and learn how to control their emotions. And very soon this control and understanding of their emotions can have a direct application to their lives outside of yoga class, helping them to figure out core issues of why they’re here and why they are suffering inside.”

After more than a decade of practicing yoga, Schweiger reports he’s a changed person. “I’m able to be in the present and I’m calmer than I can ever remember being,” he says. “I don’t need to control my physical environment and I’m much less reactive.”

And yet, despite these improvements, this vet knows there is further to go. “I still have some of the symptoms and characteristics [of PTSD]. It’s an ever-evolving process and with yoga, I can get there.”