The table was a tableau of a meal interrupted: a platter of half-eaten roast chicken, a bowl of Jap chae noodles, a can of Diet Coke tipped over on its side, and dishes slick with the residue of dipping sauces, kimchi, and pickled vegetables. They talked and they laughed as the rain poured outside. Their food grew cold and their drinks turned warm and they bobbed their heads to the music as they waited for the waitress to bring out their last dish: a bowl of soup.

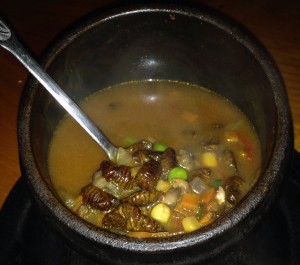

They smelled it before they saw it: salty and rich, smoky with a beefy undertone. It came in a small stone bowl on a small black plate. Bits of browns and yellows and greens floated on the surface of the steaming russet broth and someone remarked that it looked like minestrone soup. Except that it wasn’t minestrone soup. It was beondegi: vegetable soup with boiled silkworms.

“I grew up eating this,” said Howard Kim, the manager of Dan Sung Sa, as he dipped his spoon into the briny broth. “It’s more common in Korea, but you can still find it in markets or drinking spots like here.” Beondegi, he said, was one of the first dishes that was added to the menu of this late-night Korean bar (also known as a soju bar) in Oakland.

Beondegi is not a traditional Korean dish. “It’s just something we’re used to,” said Kim, a satisfying, but not-too-filling snack for people to eat when they’re drinking. But few people ever order it, he said, and those who do are usually tourists from Korea. Silkworm soup, it seems, is not as popular in America.

Howard Kim said the restaurant uses cans of boiled silkworm pupae imported from Korea to make their beondegi soup.

The silkworms used in the soup are called pupae, which refers to the non-feeding intermediate stage that comes after being larva and before adulthood. They are small and oval, the size and color of a kidney bean, with horizontal ridges encircling their bodies.

“They look like raisins, small and black, squiggly and wrinkled,” said Jessica Kim, a waitress at Dan Sung Sa who says she actually mistook them for raisins when she was a child. “But they didn’t taste anything like raisins.” She described them as salty, with a chewy outer shell that dissolves into powder once they break open in your mouth. Another diner at the table said they tasted “gritty.” Manager Kim called their flavor “earthy.”

Koreans started eating silkworms after the Korean War as a means of survival because food was scarce. “In the provinces, you had to depend on sweet potatoes, potatoes, and whatever you could find lying around,” Kim said, “and silkworms happen to be one of the items that’s very abundant.” Silkworms were already being used for their thread, but once that was removed, people started eating them as well. “A food that helped us survive became kind of mainstream,” said Kim.

Although you can buy them at Korean markets or find them on the menus of Korean drinking holes like Dan Sung Sa, silkworms have yet to catch on in the United States. But maybe silkworms, Kim said, are like cheese. “For Asians, back in the day, eating cheese was literally like eating rotten milk,” he said. “Cheese was a very hard concept historically, but now it’s found everywhere.”

Edible insects might not be as widely accepted a concept as cheese —but that could change. In fact, it’s already happening. Across the country bugs are popping up on restaurant menus and on Internet cooking shows and blogs. They’re the focus of festivals and a main ingredient in a number of proposed future foods, like granola bars and seasonings. You can definitely find bugs on the menu here in the Bay Area. Fried wax moth larvae tacos are served at the Don Bugito food cart in San Francisco and chocolate-coated fried grasshoppers made a crunchy addition to Oakland’s homemade ice creams at Lush Gelato last summer. San Francisco resident Scott Bowers founded a group for like-minded foodies—the Bay Area Bug Eating Society—back in 1999, and the poster-child of edible bug consumption, Daniella Martin, hails from the area as well.

Outside of the U.S., eating insects is no new fad. In fact, it’s been happening long enough that there’s even a fancy scientific term for it: entomophagy. Cultures around the world, especially those found in developing countries, regularly eat insects, the most common of which include grasshoppers, crickets, ants, beetles, larvae, caterpillars, cockroaches, termites, worms, scorpions, and tarantulas. According to a 2008 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, insects are eaten in 36 countries in Africa, 29 countries in Asia, and 23 countries in the Americas.

Up until now, the practice has been rare in the Western world. But proponents of entomophagy say that as people become more educated about it, the taboo will lessen, and there’s a greater possibility that bugs will show up on Bay Area dinner tables. “I think there’s a very good chance for it,” bug blogger and cooking show host Martin said. “Once [people] get past their psychological bias, there really isn’t anything to stop them.”

***

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Daniella Martin passed out edible insect food samples at Fisherman’s Wharf. She served a fried scorpion to a blonde woman and watched a little boy eat a couple dozen sautéed moth larvae. She heard someone comment that the bugs tasted like chicken and someone else remark that they were more like shrimp. Some people spit the morsels out half-chewed. Others declined her free samples. Some genuinely liked them.

For the last year, San Mateo-based Martin has been hosting these waterfront cooking demonstrations for the San Francisco Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Museum, shocking passersby with her unorthodox ingredients and spreading the word about eating insects. She does insect cooking demonstrations and presentations throughout the country, showing up in places like the Los Angeles Natural History Museum, the New York Central Park Zoo, the California Academy of Sciences, and NASA campuses. She also hosts Girl Meets Bug, an online travel/cooking show and writes bug-related articles for The Huffington Post.

Daniella Martin’s twist on the classic BLT: bees, lettuce, and tomato. Photo courtesy Daniella Martin.

Martin first learned about edible bugs during college as a major in medical anthropology when she spent nine months living in Mexico’s Yucatan studying pre-Columbian food and medicine for her thesis project. It was her favorite part of her research, she said, “the part that I always referred to when people asked me what I studied.” When she graduated, she knew she wanted to continue learning about eating bugs because she “never lost that passion for it.”

Over the years she has found that convincing people to try her bugs can be difficult. But once they do, they are usually pleasantly surprised. “When I feed them these bugs at the demonstrations I do, the majority of [people] say, ‘This is pretty good,’” Martin said. “They’re generally tasty, they’re generally nutritious, and they’re generally environmentally sound.” If people could only get over bugs’ outer appearance, she said, they’d realize how beneficial they are.

Scott Bowers, the founder of the Bay Area Bug Eating Society (B.A.B.E.S.) and a volunteer at the Randall Museum’s annual bug fest in San Francisco, believes that entomophagy has a high chance of catching on. “It’s not that it hasn’t caught on here,” he said in a phone interview last week, “it’s just that people have kind of forgotten about it.”

Like many other entomophagy advocates, Bowers believes that eating insects was a common practice for early humans, but that the practice was forgotten when they migrated from the insect-rich tropics to colder climates. “Since before we were even apes, as far back as evolution goes, humans have eaten insects,” he said. “It’s been a continuing theme throughout the history of our species.”

Martin, who said she is “obsessed” with the study of entomophagy, holds a similar belief about its origins. “Humanity has been eating insects since our very first incarnation as primates,” she said, referencing primatology research as her source. “Literally, we’ve never stopped eating bugs at any stage of development.” But most people don’t know this, she said. “It hasn’t been deemed as important,” Martin said. “It’s been deemed as insignificant, as superfluous.”

Appetizer, anyone? Daniella Martin makes finger food fun by pairing sauteed scorpions with endive. Photo courtesy Daniella Martin.

While people like Martin and Bowers have tried to advance the idea of eating insects in the states, it has proven difficult. The greatest obstacles, they have found, are cultural perceptions about bugs themselves. In the Western world, insects are viewed in a negative light and are often associated with filth and disease. People say they do not want to eat insects because they do not know where they have been, what they have eaten, or how this could translate into health risks, Martin said.

But when you apply these concerns about where your food’s food came from to other commonly eaten delicacies, the same standards do not apply, she said, especially when you think about shellfish. “It turns out that shellfish, like lobsters and crabs, generally feed off detritus, which is a fancy term for trash and rotting remains of other animals on the ocean floor,” Martin said. On the other hand, she points out, “the scorpion is eating a diet of live, healthy prey, and yet the scorpion is the one that the idea of eating makes us sick. It’s not grounded in logic. It’s grounded entirely in cultural conditioning.”

The question of how people became turned off to the practice of eating insects is something that Martin constantly thinks about. In a post on her website (GirlMeetsBug.com) last November, she speculated that a book—in fact, the most famous book in the world—might have something to do with it. “I believe the Bible was a strong influence,” she wrote, “as it says in Leviticus 11:20: ‘All winged insects that creep, going upon all fours, shall be detestable to you.’”

Cultural biases aside, entomophagy advocates have at least one thing working in their favor: environmental awareness. Compared to the environmental impacts of industrial meat processing and consumption, they say, harvesting and eating bugs is good for the environment. Shifting to bugs could decrease our dependence on raising traditional livestock, which has been proven to be a top contributor to environmental degradation due to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and resource depletion. Harvesting bugs requires less land and fewer resources, while still yielding high numbers of livestock. And unlike cows, they don’t emit the ozone-depleting gas, methane. “As we continue to put strain on the resources of this planet, people are going to have to eat more and more bugs because that’s an available food,” Bower said.

“People are more open-minded when it comes to potential environmental solutions than they have ever been,” Martin agreed, “and I think that the time is right for that reason.”

Bugs are also surprisingly nutritious. Not only are they chock full of protein—100 grams of termites contain more than half the amount of protein in a hamburger patty—but they are also good sources of vitamins, minerals, and fats, Martin said. For example, crickets and silkworm pupae are high in calcium, and water bugs and weevils are rich in iron. Most insects are also plant eaters and free of the hormones, antibiotics, and other additives that are commonly found in industrially produced meat, she said.

There are currently no U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulations regarding the consumption or sale of bugs. But bugs, Martin said, are relatively safe to eat. The combined process of freezing them (which is how they are killed) and then cooking them ensures that any parasite or bacteria they might be carrying will be killed off, she said.

Eating an insect is also different from being bitten or stung them. In other words, it’s safe to eat a scorpion, she said, but you wouldn’t want to be stung by one. “It’s not like it’s going into your bloodstream,” she said. “It’s going into your digestive system. Two totally different things.”

Outside of the Bay Area, too, the idea seems to be catching on. The Zagat Survey recently reviewed Don Bugito’s larvae tacos and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations hosted a three-day conference on insects and food security earlier this year.

“This is happening,” Martin said. “People are now more than ever really getting interested enough to invest their time and resources in it. So I think it’s going to be people talking about it, people making it available, and just keeping a presence in the media so people continually are getting their minds changed after centuries of cultural reinforcement about what insects really are.”

Entomophagy advocates frequently equate eating bugs to sushi. For decades sushi was unpopular in America, Martin said, because the public had to warm up to the idea of eating raw fish. Now, sushi is commonplace and “has enjoyed a meteoric rise in terms of cultural popularity.” With a little bit of patience, and a lot of publicity, she hopes that edible bugs will someday experience the same fate.

“Urban farming, local food, all of it,” she said. “It fits in with so many trends. Now how could you turn that down?”