A lymphoma survivor investigates disease scamming — a growing trend of faking health tragedies to rake in donations.

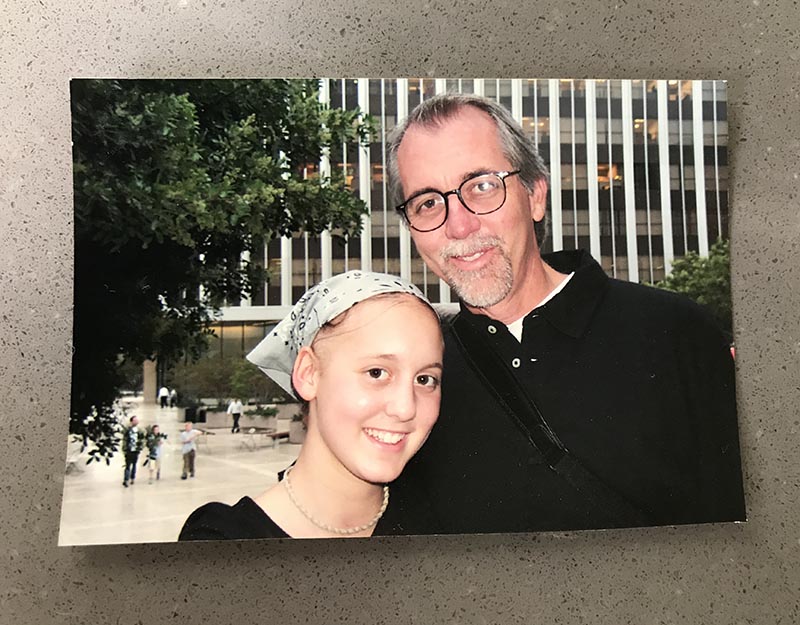

Most people didn’t know that I had cancer. They didn’t know why I stopped going to school or why I was suddenly absent from basketball practices and Bat Mitzvah classes. I was 11 years old and the last thing I wanted was to be seen as sick. I felt gross for having a tumor in my neck and weird for having a prominent medical device the size of a water bottle cap embedded beneath my left collarbone.

I was especially keen on remaining hidden during my year-long treatment. I didn’t want people — even strangers — to see me bald, bloated, and 20 pounds heavier. To conceal my scalp, I wore bandanas from the Gap, and later, when I returned to school, donned a shoulder-length brown human hair wig purchased at a hospital gift shop. To this day, I have only one picture of myself from when I had cancer. All other evidence of having been sick has since been erased.

Now things have changed. With social media and cell phones, it’s harder to keep diseases a secret from others. It’s also easier than ever to fake them — and to make a profit doing so. Pretending to have cancer isn’t something new, but it’s been made far more profitable thanks to the internet.

“Donation scammers” invite the whole town to bogus fundraisers through Facebook. They buy medical devices online, use them for selfies, and then post them on Instagram. And, with crowdfunding sites like GoFundMe and Kickstarter, they can prey directly on people’s generosity and sympathy. Victims give away their hard-earned money with a mere click.

Fortunately, there are those like Adrienne Gonzalez who knows that the internet is an easy place to perpetuate lies. In 2015, she started GoFraudMe, a blog dedicated to sniffing out fake GoFundMe campaigns. GoFundMe is easily one of the most successful online fundraising companies; a new campaign is purportedly created on the site every 18 seconds. In its first six years, it raised $3 billion in donations from 25 million donors.

In addition to those cliché “Nigerian Princes” asking for money, Gonzalez has observed all sorts of people taking part in scams, from refugees to soccer moms.

“I’ve seen scammers of all ages, education levels, sexes, different races. It could be your neighbor, your coworker, even your own mother,” she told OK Whatever in an email. “I never know what I’m gonna see!”

Bogus fundraisers, she’s noticed, tend to proliferate after large-scale tragedies as people see opportunities to concoct false narratives and capitalize off the goodwill of others. Campaigns to fund funerals are also common. People have even made up bullying stories involving their kids to make a buck.

Cancer scams, however, take the cake for being the most timeless and popular. “I’ve reported on far too many fake cancer schemes in the last two or so years,” Gonzalez said. It has its own section on the GoFraudMe website, plus a ranking of the top 10 worst fake cancer cases.

In the last few years, there have been more than a dozen reported cancer scams in the U.S. They consist of a surprisingly broad swath of people. There was the former Marine, Michael Kocher, who netted more than $9,000 online a few years ago to pay fictitious medical bills for made-up spinal tumors. More recently, a blonde sorority girl named Kelly Schmahl shaved her head, bought a wheelchair, and took selfies with oxygen tubes in her nostrils to convince others she was sick. She fleeced family and friends out of almost $10,000 before she was found out. Others include the frontwoman of a hardcore band, a Midwestern mother, a male teacher’s aide at a Texas middle school, and a bicyclist in Colorado.

Trying to understand why someone would fake cancer — why they would shear their perfectly healthy hair or pretend to be bedridden — can seem like a mystery to someone who’s been sick. But in some ways, especially from a material and financial standpoint, it’s simple: When tragedies befall someone, they’re showered with gifts and handouts from others. I certainly was.

After my lymphoma diagnosis, I received Barbies and stuffed animals, DIY beaded keychain kits, and Friends DVDs from people I’d never met and never would meet. Stores gave me discounts. Restaurants served me free desserts.

I tried to keep a levelhead about all the gifts I was receiving, but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t affected by them. During my first week in the hospital, I occupied myself by keeping a running list of all the presents people gave me titled “Things I Received.”

It’s no surprise then that making money is a motivation behind the bulk of disease scams. Receiving presents is great, and when you can swap the free teddy bears for cold, hard cash, what’s not to love?

Instead of saving their donations, scammers usually spend the money quickly. And by the time they’re caught, they usually can’t pay their victims back. Hali Etie, lead singer for the hardcore band Counterfeit, pretended to have stage 3 cervical cancer in 2015 and raised thousands of dollars through a benefit concert, T-shirt sale, and GoFundMe campaign. When her lie was uncovered, Etie — who somehow escaped charges — couldn’t return any of the funds because she’d used the funds for traveling and new tattoos.

That’s also what happened to Kocher, the former soldier who served in Syria and Iraq and who created a GoFundMe account after doctors diagnosed him with spinal tumors. When the lab results came back negative, Kocher’s doctor called to tell him the good news: He didn’t have cancer. But by that point, Kocher — who was unemployed — had already spent all of the donation money on hard, recreational drugs and living expenses. He didn’t stop collecting donations for months.

“I didn’t really know what to do,” he told Denver’s 9 News. “I didn’t know how to be like, ‘Hey, so guess what, guys? Not sick! But the bad news is I spent most of your money on heroin.’ ”

Though less common, there are also cries for attention. In the year that Schmahl, then a Delta Zeta sorority girl at Northern Kentucky University, pretended to have stomach cancer, she left the thousands of dollars she’d raised untouched in a bank account. To keep up her ruse, she’d have friends drive her to chemotherapy sessions and instruct them to wait outside while she was in the hospital. To pass the time, she’d hide on stairwells or take walks before hopping back in her friend’s car. She also set up a cell phone forwarding service so that she could pretend to be hospital staff while communicating with friends and family.

Though Schmahl diligently researched the disease online, she made a few mistakes that investigators later noticed. In pictures, she attached her chemo port in the wrong spot, and many of her bandages were clearly not applied by medical experts.

Still, no one noticed until April 2017, more than six months after she shared the news that she had cancer. Schmahl’s parents and a family friend were discussing her illness when they realized there were discrepancies to her story. When confronted, Schmahl had a mental breakdown and, according to The Tab, attempted suicide. It was only later, while being driven to the hospital, that she told the truth.

Schmahl managed to avoid jail time and community service, and was instead sentenced to five years of diversion, which is similar to probation. She’s currently serving her time in an in-patient mental health treatment facility.

The most reprehensible — and the ones that were hardest for me to learn about — were those involving children unknowingly embroiled in these scams. One Oklahoma mother raked in $20,000, orchestrating the scam from the time her daughter was only a few months old, convincing the young girl and her siblings that the young child was going to die. This went on until the girl was 4.

A Nevada mom tried the same ruse with her 11-year-old son, claiming he had leukemia and keeping him out of school for months. She raised a few thousand dollars to pay for her son’s “treatments” through GoFundMe and later pretended the boy died, turning, once again, to the internet to raise funds for his fake memorial service.

The biggest bummer about online disease scams is that it’s really hard to spot them. “What sets fraudulent fundraisers apart from legitimate ones is — wait for it — usually nothing,” read the GoFraudMe website. “You really have no way of knowing which fundraisers are legit and which are cooked up by modern day robbers using technology rather than guns.”

Still, though some may feel inclined to never donate again, Gonzalez writes on her site that, “We believe that crowdfunding — especially for personal causes — has the potential to do quite a bit of good. … That’s why we’re here, to remind everyone to donate with care.”

As for me, my cancer has been in remission for almost 20 years. I still experience the effects of my chemotherapy treatment — knee pain, weaker than normal bones, numerous scars — but I am grateful to be alive. When I hear about these disease scammers, my feelings are mixed. I’m angry, of course, at what they’ve done to other people. Saddened, too, to think back on my own experience. Yet there’s a part of me that thinks they should be grateful for the privilege of living in a healthy body. And I wish that, for them, that would be enough.